The History of Markowa

Today Markowa is a village and municipality in the Podkarpackie Voivodeship. As a village it was founded in the mid-14th century, during the reign of Casimir the Great, when German settlers were brought there. Polonisation of the language took place in the 16th and 17th centuries, and Polish national consciousness fully developed in the 19th century.

Społeczność

The settlement was big and relatively prosperous. The giving of land to local people and the introduction of self-government in the second half of the nineteenth century developed their ability to look after the affairs of the community themselves. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Markowa became one of the pioneers of co-operatives in the Polish countryside.

In the Second Polish Republic, Markowa was part of Przeworsk district located in the Lviv Voivodeship. According to the population census of 1931, over 95% of the district was inhabited by Poles, and among the national minorities there were 3.5% of Jews. At that time, Markowa was inhabited by around 4,500 people, it was a very active community, its inhabitants contributed to the establishment of the People’s University in the neighbouring village Gać in 1932. The establishment of the University resulted in an influx of intelligentsia of peasant origin into Markowa.

Markowa photographed by Józef Ulma

In the second half of the 1930s, an enlightened social milieu took shape in this agricultural commune, with various organisations made up of the local intelligentsia and the peasant elite. The community was successful in its cooperative activities, and even published a women’s magazine, “Kobieta Wiejska” [Rural Woman], whose editor-in-chief was the wife of a doctor from the Health Cooperative in Markowa - Hanna Ciekotowa. Zofia Solarzowa, later the author of the anthem of the Peasant Battalions (the underground army of the peasant movement) - “Do boju o Polska Ludowa” - was also involved in its creation.

The parish church in Markowa (from the collection of the relatives of the Ulma family)

An important centre of community life was the parish and church of St Dorothy. Thanks to the efforts of the then parish priest, Fr Władysław Tryczyński, a parish house, the so-called “Ognisko” [a youth centre], was established next to the church for the then founded Catholic Youth Association. A brass band and a fire brigade were also active at the parish. An amateur theatre troupe of the Union of Rural Youth of the Republic of Poland “Wici” was founded, in which Wiktoria Ulma also played. Among other things, the group prepared patriotic performances. After Fr Tryczyński’s death in 1936, Fr Ewaryst Dębicki became the parish priest.

The theatre group from Markowa (from the collection of Mateusz Szpytma)

The Jewish community in Markowa

The large and prosperous village also had Jewish residents. In the 1921 census, it was reported that among the population of Markowa, 126 people declared their Jewish faith, of which only 5 declared Jewish nationality, the rest declared Polish nationality. According to church statistics, in 1938 the Jewish community in Markowa numbered 107 people.

Markowa Jews had three houses of prayer (Bet ha-midrash). On major holidays, however, they went to the Łańcut synagogue. Their houses were scattered throughout the village, but in the western part of Markowa, known as Górna, three Jewish houses stood side by side, commonly referred to as a colony. In the part identified as Dolna, located to the east of the church and south of the Markówka river, seven Jewish houses stood along a side street a kilometre long, next to Polish ones. This is why the district was called Kazimierz, after Krakow’s Kazimierz, where mainly Jewish people lived. The name is used in Markowa to this day.

The Jews of Markowa, like other Jews in other localities, were mainly engaged in trade. Relations between Poles and Jews were basically good. However, religious and cultural considerations meant that the two communities lived side by side without intermingling. According to data just before the outbreak of the Second World War, in the school year 1938/1939, 22 Jewish pupils attended the village school in Markowa. Józef Ulma was on very good terms with the Jews already before the war. Several Jewish families lived next door to him, and he traded the vegetables he grew with others.

The German occupation

A dramatic chapter in the history of the village began with the outbreak of the Second World War. After the occupation of Poland, the Germans introduced a new administrative division. Although the previous division of municipalities and communes was maintained, rural and municipal self-government was abolished. The function of the commune head (vogt) and village head, who reported directly to the German officials, was left in place.

Life in the village changed. Curfew terror, quotas, public order duty, deportation to work in Germany, conscription of young men into the Building Service became a daily occurrence. As 70% of the population had German surnames, the Germans wanted to Germanise them, but the agitators urging people to sign the folksliste did not achieve any results.

At that time, the Union of Armed Struggle and later the Peasants’ Battalions (BCH) were established in Markowa. The municipal post of the Home Army in Markowa had the code name “Marian” in the military structure. It belonged to the Przeworsk District. Antoni Dźwierzyński “Ryś” became the commander of the post in the municipality. In the whole municipality (before the Peasants’ Battalions and Home Army merged) there were about 100 Home Army members.

The activists of the People’s Party and the Union of Rural Youth of the Republic of Poland “Wici” in Markowa established underground party structures in the municipality and the village, the so-called threes. In 1942, there were also municipal structures of the Peasants’ Battalions (commanded by Michał Ulma “Kamień”), and later also the People’s Security Guard (led by Mieczysław Pelc “Kożuchowski”). Two Peasants’ Battalions platoons were formed in Markowa, with a total of 74 men.

At the outbreak of the war, at least 120,000 Jews lived in Podkarpacie, the region in which Markowa is located.

The Germans began to introduce anti-Jewish laws in the occupied Polish territories in the very first months of their rule. On 23 November 1939, an order was issued in the General Government requiring all Jews over the age of ten to wear an armband with the Star of David. They were further imposed to work, prohibited from using means of transport and leaving their place of residence without permission. Assets, businesses, shops and workshops were confiscated. Soon this oppression was combined with deprivation of liberty - a large part of the Jewish population was sent to labour camps, of which there were already about 200 in 1941. The remaining Jews were placed in ghettos, with more than 400 established in the occupied Polish territories.

In 1941, the authorities of the Third Reich decided on a “final solution” of the Jewish question, which in effect meant a will to murder all European Jews, including those who lived in large numbers in German-occupied Poland. As a result of the aforementioned decision - approx. 5.5 million European Jews died in mass extermination camps, as a result of shootings, forced devastating labour, starvation and disease caused by the conditions created by the occupying forces.

As in other parts of the General Government, anti-Jewish laws were quickly introduced in the Markowa area. In the first days of the occupation, the Germans burnt down the synagogue in Przeworsk and intended to destroy the synagogue in Łańcut, but the latter was saved thanks to the intercession of the entailer of Łańcut, Alfred Potocki. It became impossible for Jews to practice most of the professions from which they had made a living before the war.

In the second half of 1941, the creation of ghettos began in the Rzeszow region. By the summer of 1942, 17 ghettos were established, some of which were closed areas, as were the ghettos in Warsaw and Krakow.

The Germans soon set about the final liquidation of the Jewish community. From mid-July to mid-December 1942, in the eastern part of the Krakow district, they carried out the “Reinhardt” operation, which was led by the chief of staff of the SS and police command of that district, SS-Hauptsturmführer Martin Fellenz. Jews were then deported from some villages to towns for selection. Those who were young and healthy were sent to labour camps, the others were murdered or transported to the extermination camp in Bełżec, which became the largest site of martyrdom for the Jews of the Podkarpackie region. In many villages, Jews were shot without selection. This is what happened in the Jarosław starosty. From some towns, such as Łańcut, Leżajsk or Radymno, in July and August 1942, Jews were sent to the camp in Pełkinie, from where they were deported after a few weeks to Bełżec.

For the Jewish inhabitants of the towns, the second half of 1942 was the last moment when they could try to escape and find a hiding place in bigger groups. Later on, only individual people could do it. During this time, refugees from the cities also appeared in Markowa.

Nevertheless, it was not safe there either. Many Markowa residents recall that even before Operation Reinhardt, German officers carried out numerous robberies and murdered Jews.

Most often these crimes were committed by a senior constable from Markowa, Konstanty Kindler, a Volksdeutsche originally from Wielkopolska. He saw this as a path to promotion and a reward in the form of serving in the German gendarmerie. He often came to the Goldmans, one of the wealthier Jewish families, and demanded money and various material goods from them. After such visits, Estera Goldman, sensing a bleak future, told her neighbours: “We Jews will go for breakfast, you Poles are going for dinner”.

It is likely that several to a dozen Markowa Jews, including Beniamin Müller’s family of seven, perished at the hands of the Germans at the time. Miraculously, the teenage Ida Goldman was saved, who, at the moment of the execution of her family, broke away from the executioners and escaped into the fields. She was spotted by Franciszek Domka, a Home Army soldier from Nowosielec, thanks to whom she survived the war. Domka took care of Ida and gave her to a childless Polish couple to raise.

In the spring of 1942, Jews living in Markowa were obliged to apply for kenkarts (identity cards). As a result, they were accurately recorded.

At the beginning of August 1942, in Łańcut and its surroundings, the Germans began Operation Reinhardt, whose main executor was the German gendarmerie. The intention was first to gather all the Jews in the camp in Pełkinie, then to transport some to the extermination camp in Bełżec, and to execute the rest on the spot. Jews began to be deported from Łańcut, as well as from the surrounding villages, including Markowa. In August, the Germans imposed a ban on Jews staying in Markowa. The German gendarmerie, which arrived every few days, checked that this was being observed.

Also in August, the Germans ordered local peasants to come with their carts to transport Jews, telling them that they were taking them to work. Probably most of them understood by then that this was the road to extermination. Despite this, according to various figures, 6 or 8 Jews from Markowa turned up for the German call. Dozens of others, expecting repressions for failing to comply with the order, fled from their homes into the fields or hid in their neighbours’ buildings, sometimes with their consent and sometimes without the knowledge of their hosts. Those seeking shelter outside the village would return to the village in the evenings, asking for food and accommodation.

One group hid in the woods in Husów, another, a family of four called Ryfki, with the help of Józef Ulma, built a shelter in the ravines near the stream. At least one Jewish family (the Riesenbachs) was warned of deportation by two blue policemen from the local police station Nonetheless, many peasants were afraid to provide any help, knowing that doing so would result in the death penalty. There were also those who, obeying German orders, led Jews to the blue police station.

The situation was made more difficult by the fact that German gendarmes, together with the blue policemen, carried out ad hoc searches for Jews hiding in the village.

The Germans realised that, despite their orders, many Jews still remained in Markowa and other villages, as well as in the surrounding fields and forests. At the beginning of December 1942, they organised a search in neighbouring Husów and soon also in Markowa.

On Sunday 13 December, they ordered the village head, Andrzej Kud, to undertake a search for hiding Jews. The village head could not, without risking severe repression, including the death penalty, refuse to carry out the order, but, what is important, on that day before noon he publicly informed the residents about the action (every Sunday he made announcements in front of the church). Warned in this way, the farmers who were hiding Jews were able to take extra care and better camouflage their hiding places. It is known that immediately after returning from church, the family of Józef and Julia Bar, with whom the Riesenbachs were hiding, did so, and that Franciszek Bar prepared a new hiding place for Jakub Einhorn.

Following the German order, the village head appointed firemen, guards and district officers to search for the hiding Jews. If they refused, they were threatened with the death penalty. The latter were expected to select people in their areas who had to take part in the search.Following the German order, the village head appointed firemen, guards and district officers to search for the hiding Jews. If they refused, they were threatened with the death penalty. The latter were expected to select people in their areas who had to take part in the search.

Witnesses interviewed after the war most often reported that it was mainly firemen who took part in the activities described (this is also confirmed by accounts collected much later, in 2003), in addition to guards, hostages, district officers and sometimes “civilians”. The latter included the aforementioned hostages and district officers.

It is difficult to determine precisely how many people took part in the search for the hiding Jews, but there were at least 26. Given what had happened a few days earlier in Husów, the searchers must have been aware that the captured Jews would be murdered by the Germans. The tracking of hiding Jews was carried out on German orders. It was not possible to establish the exact number of people caught on 13 December. There were probably 25 of them. However, it can be ascertained that the Einhorn siblings - Markiel, Abraham, Nuchym, as well as their two sisters of unknown names, Rywka Tencer with her two daughters and a granddaughter, Zelik with his wife and two children, the Najderg family and a man hiding with false documents issued in the name of Stanisław Ciołkosz were among them.

The blue policemen locked the captured Jews in the communal detention centre, located at the main intersection in Markowa. There they were held all night from 13 to 14 December. The next morning German gendarmes arrived in the village. They brought out all the detainees and shot them in a former trench.

The Righteous from Markowa

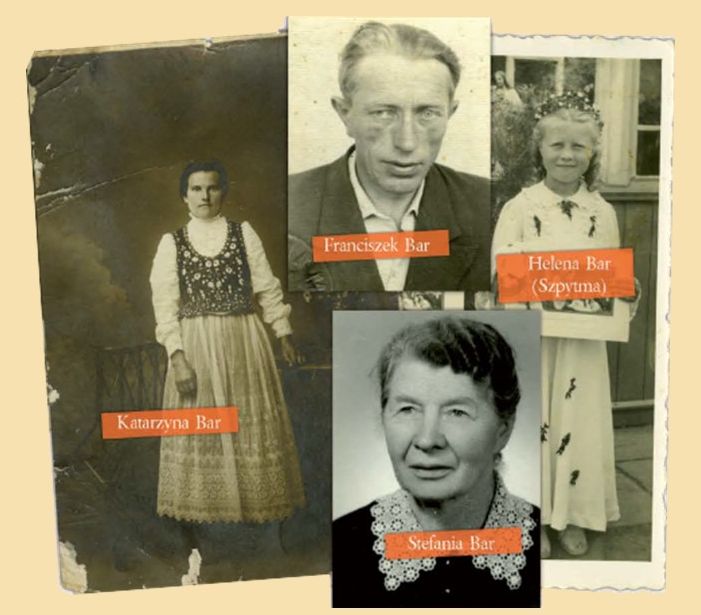

After the events of December 1942, many peasants in Markowa continued to give shelter to Jews in defiance of German prohibitions. Michał and Maria Bar, who lived with their children Stefania, Janina, Weronika, Antonina and Antoni, hid Chaim and Ruzia Lorbenfeld and their daughter Pesia.

The already mentioned Józef and Julia Bar, living with their daughter Janina, were hiding the Riesenbach family: Jakub and Ita and their son Josek and daughters Gienia and Mania.

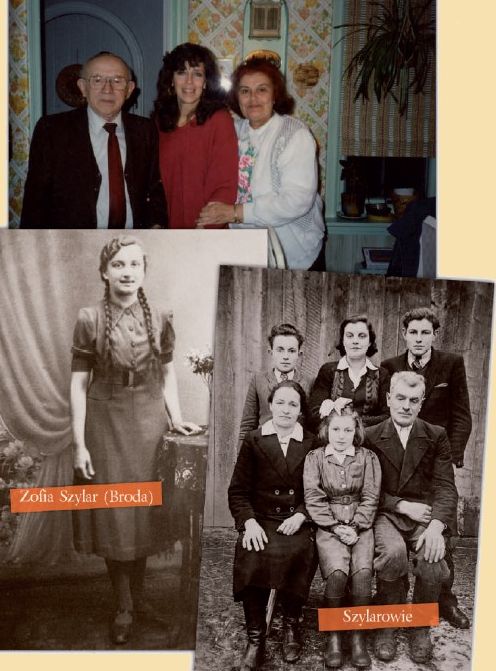

At the home of Antoni and Dorota Szylar, who lived with their children Zofia, Helena, Eugeniusz, Franciszek and Janina, six members of the Weltz family had been hiding since January 1943: Miriam and her children Moniek, Abraham, Reśka and Aron, as well as the latter’s wife Shirley, and after a few months they were joined by Aron and Shirley’s son Leon, who was a few years old.

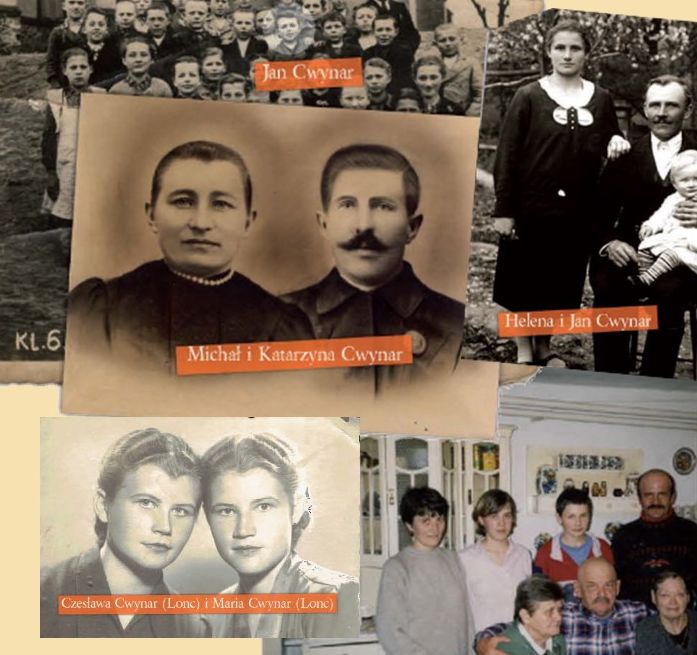

At the home of Michał and Katarzyna Cwynar, who were raising their grandson Jan, a Jew using the name Władysław survived (perhaps it was Mozes Reich, who testified after the war that he had been hiding in Markowa).

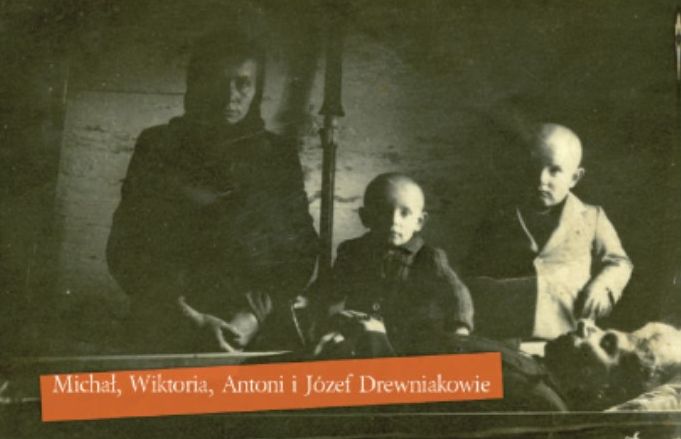

Jakub Einhorn initially hid in Husów and Sietesza, as well as in Markowa, where he had several hiding places. At first, he was assisted by Michał and Wiktoria Drewniak, who lived with their children Antoni and Józef, as well as by Katarzyna Bar and her son Franciszek and daughter Stefania (the latter was raising her daughter Helena at the time). After the death of Michał Drewniak in 1943, Jakub Einhorn found new shelter with Jan and Weronika Przybylak, who lived with their children Bronisław and Zofia. According to a post-war account by Eugenia Einhorn, Jakub’s widow, a Jewish family of three who were friends of Einhorn were also hiding with the Przybylak family.

From the summer of 1943, Abraham Segal, who claimed to be Roman Kaliszewski, stayed and worked on the farm of Jan and Helena Cwynar, who lived with their daughters Maria and Czesława.

Correspondence dating as far back as the 1950s shows that his employers became aware of his Jewish background after a while, but continued to hide him. This was all the more dangerous because Cwynar was at that time a member of the leadership of the underground folk movement in Przeworsk district, and one of the denunciations that was intercepted stated that “he was a subversive folk provocateur”.

The largest group of Jews hid with the Ulma family. They, as the only ones in Markowa, suffered the harsh consequences. They were murdered by the Germans along with the people they were helping. (find out more).

The sacrifice of the Ulma family was not in vain. Thanks to people like them, tens of thousands of innocent people destined for extermination by the occupying forces survived. In Markowa, other farmers saved 21 Jews. Despite the execution, which was carried out almost in front of their eyes, they did not relent and did not throw out those in hiding. The Ulmas and all the others who helped the Jews bore witness to the fact that a man is prepared to sacrifice even his own life in the name of love for his neighbour.

Bibliography:

- M. Drożdż-Szczybura, Wybrane problemy ochrony krajobrazu kulturowego polskiej wsi na przykładzie Markowej w woj. podkarpackim, Kraków 2000, s. 11.

- M. Szpytma, Świadomość narodowa chłopów polskich w Galicji w latach 1867–1914, Kraków 1999 (na podst. pracy magisterskiej obronionej na Uniwersytecie Jagiellońskim).

- T. Szylar, Markowa – wieś spółdzielcza [w:] Z dziejów wsi Markowa, red. J. Półćwiartek, Rzeszów 1993, s. 211-241.

- Drugi spis powszechny ludności z dn. 2 XII 1931 r. Mieszkania i gospodarstwa domowe – Ludność – Stosunki zawodowe – Województwo lwowskie bez miasta Lwowa, Warszawa 1938, s. 38-39.

- Z. Anders, Z dziejów kultury i życia literackiego [w:] Z dziejów wsi Markowa…, s.247-252.

- Skorowidz miejscowości Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej opracowany na podstawie wyników Pierwszego Powszechnego Spisu Ludności z dnia 30 września 1921, t. 13: Województwo, Warszawa 1924, s. 34. W Markowej mieszkało także 11 grekokatolików, z których 2 podało narodowość ruską.

- Mateusz Szpytma, Sprawiedliwi i ich świat w fotografii Józefa Ulmy, Wydanie 3, zmienione, Warszawa 2023, 168 s., ISBN 978-83-8229-842-0